Communities throughout the U.S. face challenges related to sustaining a health care workforce and providing health care. These concerns are especially relevant to Missouri and its rural areas due to the state’s poor health outcomes, workforce shortages and lack of health care facility availability.

The health care industry contributes to community sustainability and economic growth, and it serves as a primary employer in many communities. As the largest employment sector in the state, Missouri’s health care and social assistance sector employed 15% of working Missourians in 2020. Government, including public schools, ranked as the next largest sector and employed just less than 15% of working Missourians.1

This publication highlights rural-urban differences in Missouri’s health outcomes, health care workforce and availability of care. It provides context that community stakeholders and health care industry professionals can use to sustain and grow Missouri’s health care sector and improve health outcomes in rural and urban Missouri.

Missouri health behaviors and outcomes rank poorly

Of all U.S. states, Missouri ranked 38th in an index that accounts for health behaviors and health outcomes including social and economic factors, physical environment and clinical care in 2020.2 Missouri’s relatively low ranking is principally attributed to health behaviors (e.g., poor nutrition, low physical activity, tobacco use), less access to care and high frequency of multiple chronic conditions.

- In 2019, 11.2% of Missouri’s adults reported having multiple chronic health conditions such as arthritis, asthma, kidney disease, pulmonary disease, cardiovascular disease, cancer, depression or diabetes. The national average was lower at 9.5%.

- In the same year, 17.1% of Missourians met the federal physical activity recommendation, which states Americans should participate in 150 minutes of moderate exercise per week. The national average was higher at 23%.

- In 2020, 19.6% of adult Missourians smoked. The national average was lower at 15.9%.

- In 2020, 34.8% of Missourians were obese. The national average was lower at 31.9%.

Rural health outcomes and behaviors are worse than those in urban areas

Within Missouri, rural health outcomes are poorer than urban outcomes. Rural Missourians had a shorter life expectancy on average compared with urban Missourians in 2014 and 2015 — 76.5 years in rural areas compared with 77.9 years in urban areas.3 Other poorer health outcomes in rural Missouri have included working-age mortality, emergency room visits, smoking, physical activity and obesity.4

The reasons for Missouri’s rural and urban health outcome discrepancies are multifaceted. Poverty and advanced age partly contribute to the differences.

- Poverty is more prevalent in rural parts of the state. In 2015, 17% of Missouri’s rural population lived in poverty compared with 13.6% of its urban population.3

- Missouri has a disproportionately older rural population. From 2012–16, 34.2% of Missourians who were 65 years old and older lived in rural areas. For comparison purposes, 29.3% of all Missourians lived in rural areas.5

Labor shortages and facility access shape health care availability

Missouri has a lower ratio of primary care providers per capita than the U.S. This may be driven by a lack of health care facility access in some Missouri regions and difficulties related to health care worker recruitment and retention. For example, seven rural hospitals have closed in Missouri since 2014; many cited financial challenges. These closures adversely impact health care availability for rural Missourians.

Missouri has high demand for health care workers

Because it is one of Missouri’s largest employment sectors, health care highly demands workers. During second-quarter 2021, Missouri had more online job postings for registered nurses than any other occupation.6 To meet the population’s health care needs, the health care industry depends on workers with a variety of skill levels and educational backgrounds. In a survey of health care employers, 49% reported a shortage of employees skilled in patient care.7

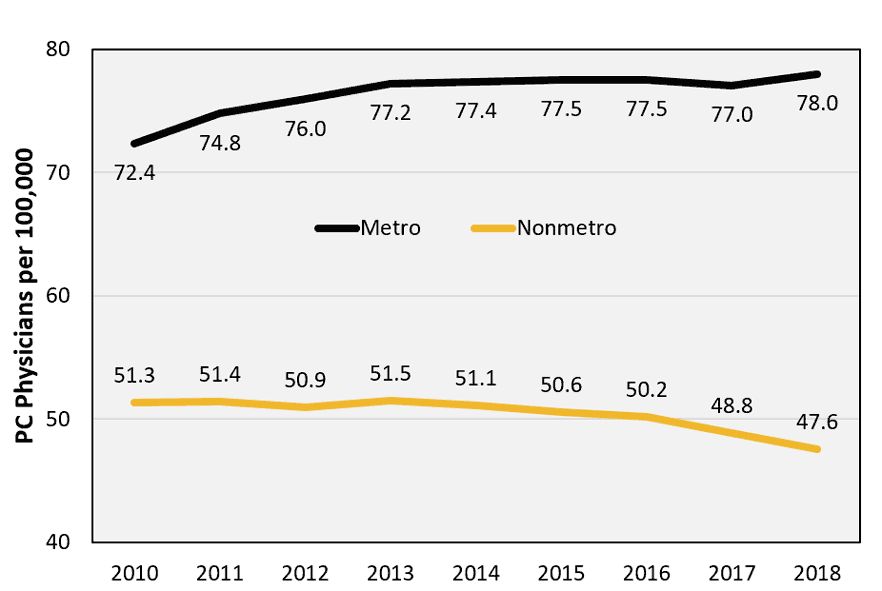

For metro and nonmetro Missouri, Figure 1 shows the ratio of primary care physicians per 100,000 people from 2010–18. Compared with the U.S. average, Missouri had a lower ratio in metro and nonmetro counties. In 2018, Missouri metros had 78 primary care physicians per 100,000 residents compared with 80 primary care physicians per 100,000 people for the U.S. The Missouri-to-U.S. gap for rural primary care physicians was 47 per 100,000 people to 52 per 100,000 people. Not only does Missouri fall short in access to primary care, but a gap also exists between the state’s metro and nonmetro places — consistent with the gap found nationally.

Figure 1. Missouri Primary Care (PC) Physicians per 100,000 People, 2010–18. (Source: MU Extension Exceed figure created from U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration Area Health Resource Files)

Support occupations have high job vacancies

Missouri’s health care workforce employee turnover rate, which measures the rate at which employees leave a workforce and are replaced, reached an all-time high of 19.5% from 2015–19 — before the COVID-19 pandemic had begun. Hospital jobs with the highest vacancies were licensed practical nurses, housekeepers, staff nurses, surgical technicians and sterile processing technicians. These support positions often have the highest turnover rates. Two factors in particular challenge hospital employee retention: competitive pay from other industries and shallow labor pools.6

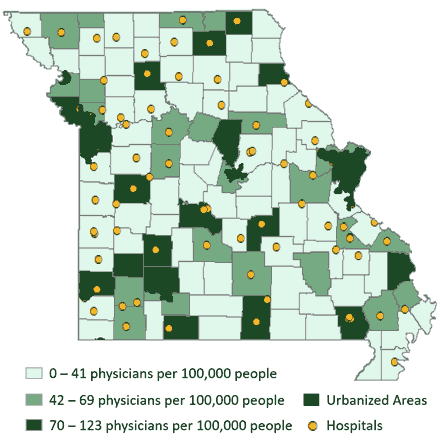

Rural parts of Missouri lack access to health care facilities

Figure 2. Rural Missouri Hospital Locations as of April 5, 2021. (Source: MU Extension Exceed map using U.S. DHS Homeland Infrastructure Foundation-Level data)

Figure 2. Rural Missouri Hospital Locations as of April 5, 2021. (Source: MU Extension Exceed map using U.S. DHS Homeland Infrastructure Foundation-Level data)

Southern and northeastern Missouri contain clusters of counties without hospitals (Figure 2). Approximately 11% of Missouri’s population lives in a county with no hospital. For people in these counties, drive times to hospitals average 30 minutes to 45 minutes.8

Primary care provider shortages exist throughout Missouri

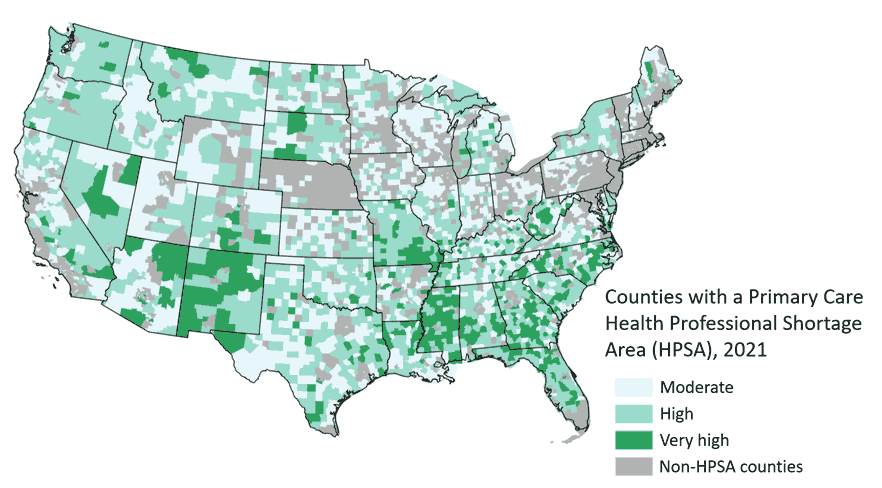

Compared with neighboring states, a higher proportion of Missouri counties in 2021 had a primary care provider shortage area that met the Health Professional Shortage Area (HPSA) criteria defined by the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration (Figure 3). One must apply for HPSA designation, and HPSA scores correlate with less primary care physician access. Four factors determine HPSA scores:

- Population-to-provider ratio,

- Percent of the population below 100% of the federal poverty level,

- Infant mortality and low birth weight rates, and

- Travel time to nearest source of care.

Figure 3 shows that most Missouri counties in 2021 had a primary care provider shortage area — demand for primary care providers exceeded supply. Areas around Kansas City and St. Louis were exceptions. Southeast Missouri had the highest HPSA scores, indicating the greatest need for primary care providers in those rural counties.

Access to primary care improves life expectancy and serves as the first step to eliminate health disparities. Missouri’s rural-urban gap in primary care access exacerbates lack of access to specialists who can address specific health concerns such as heart disease, diabetes, maternal care and kidney failure. Figure 3 excludes mental health, dentistry or specialized physician shortages (e.g., nephrologists, cardiologists, oncologists and endocrinologists).

Figure 3. Primary Care Health Professional Shortage Area (HPSA) Scores in part or all of each county, 2021. (Source: MU Extension Exceed map using data from the Health Resources and Services Administration). Note: Higher score suggests higher need for primary care health providers in at least part of a county. Grey counties are those without any primary care health professional shortage areas.

Health care entrepreneurship may be a solution

Research suggests that primary health care provider turnover is lower when providers practice as self-employed physicians instead of work as wage or salary employees.9 For self-employed primary health care providers, leaving their communities may mean losing the time and financial capital they invested to establish their businesses and build a patient base. Providers who commit to establishing a practice may also form long-term trust within the community. Thus, so-called health care entrepreneurship may improve primary care provider availability in some communities. Expenses such as malpractice insurance, however, have discouraged health care entrepreneurship.

One potential solution to the primary care provider shortage may be to expand, through entrepreneurship, the prevalence of nonphysician primary care providers such as nurse practitioners and physician assistants. These providers could extend the reach of traditional physicians, particularly in rural areas. The National Academy of Medicine recommends that states permit nurse practitioners to practice medicine independent of oversight by another health provider. Missouri is one of 11 remaining states restricting the ability of nurse practitioners to practice independently. Allowing nurse practitioners to practice independently, as self-employed entrepreneurs, in Missouri may induce nurse practitioners to start their own practices and serve their communities.10

Health care plays a role in local economic development

Because the health care and social assistance sector accounts for 13% of jobs in Missouri’s rural counties, the sector may facilitate economic development through investments in rural infrastructure, workforce and community building.

When health services are offered locally, rural residents may be more likely to stay in the community for care. If they instead drive to urban areas for care, then rural residents during those trips may spend money in restaurants and stores located outside of their home communities.

Health care provision may also benefit economic development because firms consider this factor — along with other quality of life factors such as available housing and schools — when deciding where to locate. Thus, having access to quality health care may attract and retain businesses in a region.

Endnotes

- 2020 QCEW jobs by two-digit NAICS. Source: EMSI.

- Information regarding Missouri and U.S. health behaviors and outcomes in this paragraph and the following paragraph is from the United Health Foundation’s America’s Health Rankings.

- Information on health disparities between rural and urban Missouri comes from the 2017 Biennial Report of Health in Rural Missouri (PDF) from the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services Office of Primary Care and Rural Health.

- This paragraph uses an uncommon definition of rural. Urban counties are defined as those with a 2013 population density of greater than 150 persons per square mile plus any county that contains at least part of the central city of a Census-defined metropolitan statistical area. Using this definition, 13 Missouri counties and St. Louis city are urban. Missouri’s other 101 counties are rural.

- Information collected from the U.S. Census Bureau’s America Counts publication, Older Population in Rural America.

- Missouri Economic Research and Information Center’s Real Time Labor Market Summary. Missouri, April–June, 2021. Retrieved Oct. 8, 2021.

- Survey conducted annually by Missouri Economic Research and Information Center.

- Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services Office of Primary Care and Rural Health “Healthcare Delivery Sites in Rural Missouri (PDF),” 2017.

- Kuhns, Maria. 2021. Insights for rural health care provider retention: a quantitative survey analysis. MS Thesis.

- More information on state practice environments for advanced practice providers such as nurse practitioners and physician assistants.